A student is having trouble engaging in class work and often leaves their chair to go talk to others. They forget to turn in their homework and when they do, seem to make a lot of mistakes and struggle to follow directions. They struggle to sit in their seat and often blurt out answers. Teachers often write home saying they are “not living up to their potential.” Who are you picturing? What does the student look like? What gender came to mind? For most of us, it would be a boy.

March 8th is International Women’s Day and the focus for this year is “Inspire Inclusion.” As a clinical psychologist who works with Black and/or Latina/é/o youth with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and their families, I have seen firsthand how girls and women with ADHD are underdiagnosed, not believed, and not treated adequately. This International Women’s Day, I call in providers, parents, educators, friends, family, and everyone who has loved a woman with ADHD to increase awareness about ADHD in women.

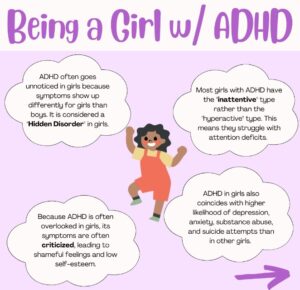

ADHD is a neurodevelopmental diagnosis that includes difficulties with executive functioning, shifting and sustaining attention, restlessness, and impulsive choices. Worldwide, the diagnosis rate of men with ADHD is 2.5 times higher than women despite likely equal rates of diagnosis for men and women (Cortese et al., 2023; Littman, 2021). The main issue is that there are many stereotypes about ADHD that bring to mind a hyperactive boy and the symptoms in the DSM-5 support those stereotypes (Barkley, 2023). This leads to inequities in diagnosis and treatment and increased likelihood of other mental health difficulties. Girls are more likely to receive a later in life diagnosis of ADHD, which leads to low self-esteem and higher rates of anxiety and depression (Attoe & Climie, 2023). Girls and women with ADHD are also more likely to exhibit symptoms of inattention, something clinicians, teachers, and parents report struggling to identify as it is more internal and not as disruptive (Lynch & Davison, 2022; Quinn & Wigal, 2004). The world socializes women and girls to be polite, obedient, and organized, and when women present differently, they are punished for disruptive behaviors more severely than boys (Holthe, 2013). This leads to masking of symptoms, which is a heavy cognitive load.

These biases lead to girls and women not being referred to ADHD services and treatment. Often, women and girls seek treatment for a secondary diagnosis, a diagnosis that has occurred because of their undiagnosed ADHD, like anxiety and depression and must fight for an ADHD diagnosis (Attoe & Climie, 2023). This assumes a significant amount of self-awareness and mental health literacy, something that puts an additional burden on girls and women. Societal expectations for women are burdensome enough without this additional layer.

There are multiple systems in place where we can work to increase awareness of ADHD in girls and women to support and allow them to thrive.

Education System

- Provide training to teachers, school staff, counselors, and others who work with students on the differences between girls and boys with ADHD. This includes noticing inattentive and more internalized behaviors.

- Provide all students with mental health assessments.

- Create inclusive classrooms that are neurodivergent friendly, like active learning and play being incorporated in class.

- Flexibility in homework and deadlines.

Health System

- Train all mental health providers on the symptomology of ADHD. As a child psychologist with a focus on supporting and serving people with ADHD, I’m aghast at how few providers truly understand or feel confident in diagnosing and treating ADHD, let alone understanding the nuances and variability in ADHD in girls and women. We must do better in our education of clinicians.

- Educate providers on adult ADHD. There are many providers (e.g., psychiatrists, psychologists, primary care doctors, etc.) that still believe that ADHD suddenly disappears when someone turns 18. As ADHD is a neurodevelopmental diagnosis, this is not the case. We must repair the damage that has been done by this belief.

- Train all pediatricians to look for and ask about inattentive symptoms.

- BELIEVE GIRLS AND WOMEN. Women are less likely to be believed about symptoms for any diagnosis, so we must uplift and truly value their lived experiences.

- All providers, please educate yourselves on the fact that all people with ADHD, but girls and women in particular, can be “good at school/work,” “smart,” and “successful” and still have ADHD. Being successful in a neurotypical world is something all people with ADHD must face and unfortunately many people are not believed about their symptoms due to being successful.

- Diagnostic interviews for ADHD should include the following:

- Trauma, including interpersonal, developmental trauma disorder symptoms (Ford et al., 2022; van der Kolk et al., 2009), discrimination related trauma, and chronic stressors. Just screening for PTSD and/or ACEs is not sufficient as research has shown women with ADHD experience higher rates of trauma (Chronis-Tuscano, 2022).

- Non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) and suicidality questions. Girls and women with ADHD have higher rates of NSSI and SI, thus, we need to better address these concerns.

- Eating disorder questioning.

- Sexual activities. Girls and women with ADHD are more likely to engage in risky sex behaviors and experience unplanned pregnancies.

- Masking! We all need to ask about masking when discussing ADHD symptoms as many people regardless of gender mask their ADHD symptoms. Due to societal norms, girls and women have a higher burden of masking their symptoms as many ADHD related behaviors are not associated with how women in our society are expected to act. This increases the cognitive load and leads to higher rates of secondary-to-ADHD mental health diagnoses.

DSM-5/ICD11 specific changes

- Change the diagnostic symptomology to be better reflective of symptoms in girls and women (Barkley, 2023). This will increase understanding for providers.

- Increase age of onset of symptoms (Littman, Hinshaw, & Chronos Tuscano, 2023).

- Currently impairment is examined in relationships, school/work, and home life. We must also include information on how distressing symptoms are to people with ADHD as part of the impairment criteria.

- When asking about how symptoms of ADHD impair relationships, it is important to ask about ability to form close relationships, experience of abuse, experiences of rejection from others, unintentionally saying things that were considered hurtful/inappropriate, and whether they experience shame when comparing themselves to peers (Attoe & Climie,2023). These are experiences women with ADHD frequently have, but do not often get asked during diagnostic interviews.

With this blog I hope you have learned about how women with ADHD experience their diagnosis differently and if you are a provider, will work to make changes in your practice.

Of note, this blog is focused on inequity, which typically leaves a negative tone and focuses on the difficulties women with ADHD face. I want to end by saying women with ADHD are some of my favorite people because despite all these burdens set in place by society and institutions, they can be smart, caring, fun, creative, and bring divergent thinking to the world that makes true change. I recommend following some amazing women with ADHD who provide ADHD content, including Rach Idowu (@AdultingADHD), René Brooks (@blkgirllostkeys), Dani Donovan (@DaniDonovan), Ying Deng (@ADHDAsianGirl), Dr. Mariely Hernandez (@DrMarielyH), @theADHDAcademic, and my team @ACCTIONLab/@DrZoeRSmith!

NB this blog has been peer-reviewed

References

- Attoe, D.E., & Climie, E.A. (2023). Miss. Diagnosis: A systematic review of ADHD in adult women. Journal of Attention Disorders, 27(7), 645-657. https://doi.org/10.1177/10870547231161533 Barkley, R. (2023) DSM-5 ADHD Criteria Is Flawed: How to Better Diagnose Symptoms (additudemag.com)

- Cortese, S., Song, M., Farhat, L.C. et al. Incidence, prevalence, and global burden of ADHD from 1990 to 2019 across 204 countries: data, with critical re-analysis, from the Global Burden of Disease study. Mol Psychiatry (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-023-02228-3

- Chronis-Tuscano, A. (2022), ADHD in girls and women: a call to action – reflections on Hinshaw et al. (2021). J Child Psychol Psychiatr, 63: 497-499. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.13574

- Ford JD, Spinazzola J, van der Kolk B, Chan G. Toward an empirically based Developmental Trauma Disorder diagnosis and semi-structured interview for children: The DTD field trial replication. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2022; 145: 628–639. doi:10.1111/acps.13424 Hinshaw, S., Littman, E., & Chronis-Tuscano, A. (2023). ADHD in Women and Girls: How Symptoms Present Differently in Females (additudemag.com)

- Hinshaw, S.P., Nguyen, P.T., O’Grady, S.M., & Rosenthal, E.A. (2022). Annual research review: Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in girls and women: underrepresentation, longitudinal processes, and key directions. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.13480

- Holthe M. E. G. (2013). ADHD in women: Effects on everyday functioning and the role of stigma [Master’s thesis, University of California, Berkeley]. NTNU Open. Littman (2021). ADHD in Women: Misunderstood Symptoms, Delayed Treatment (additudemag.com)

- Lynch A., Davison K. (2022). Gendered expectations on the recognition of ADHD in young women and educational implications. Irish Educational Studies. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/03323315.2022.2032264

- Quinn P., Wigal S. (2004). Perceptions of girls and ADHD: Results from a national survey. Medscape General Medicine, 6(2), 2. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1395774/#__ffn_sectitle van der Kolk, B.A., Pynoos, R.S., et al. (2009). https://complextrauma.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Complex-Trauma-Resource-3-Joseph-Spinazzola.pdf